Dayna Cunningham, Omidyar Dean of the Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life, recalls the moment when offshore wind power sparked her imagination.

She was talking with Eric Hines, professor of the practice and director of the School of Engineering’s graduate programs in offshore wind energy engineering, about a student-led report on the economic and ecological advantages of low-carbon concrete foundations for offshore wind turbines, compared with steel.

A key finding of the report: one of the strongest drivers behind offshore wind development in the U.S. is the desire to create high-quality jobs that can support a diverse and inclusive workforce.

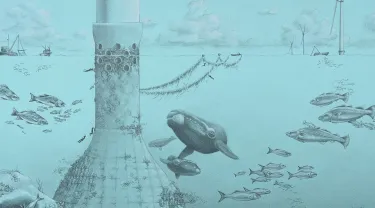

But it was the report’s cover illustration, says Cunningham, that made a strong first impression. Cameron Barker, a recent graduate of the School of the Museum of Fine Art at Tufts, had worked with Hines and a team of engineers, ocean scientists, marine biologists, and humanists to envision an underwater wind turbine support structure that was surrounded by an abundance of ocean life—a vision of a future in which offshore wind drove the regeneration of the seabed, created well-paying jobs, advanced clean energy, and improved community health.

All these factors, says Cunningham, “are more than just desired. They define a just and equitable energy transition.”

With that point underscored, she knew that offshore wind power progress went well beyond technology; it brought the industry to her wheelhouse.

“It is important to try to build a transparent set of ideas about how this energy transition trajectory might unfold,” Cunningham says. “It’s important for society as a whole that we eliminate the uncertainty and help people feel engaged and informed.” That dovetails well with the mission of Tisch College, she adds, where a wide range of programs promote the civic and political engagement of young people in communities and in democracy.

Now, thanks to a new partnership with Cunningham and Tisch College, Tufts’ programs in offshore wind will be able to expand understanding of how rapid technological progress can cause profound social change for the better, says Hines, the Tsutsumi Faculty Fellow in Civil and Environmental Engineering.

“The transition to clean, renewable energy goes beyond engineering—it also encompasses larger social questions that speak to the democratic process,” he says. “It’s not enough to train a skilled workforce. We want to use the strength of collaboration here at Tufts, and our national reputation in civic leadership, to develop ideas and initiatives that advance the public good.”

That partnership debuted this summer through the Tisch Summer Fellows and Freedom Summer programs. Tisch Summer Fellows Bridget Moynihan, EG25, and Sebastian Barajas Ortiz, E25, collaborated with the Salem Alliance for the Environment to support early conversations tied to the Salem Offshore Wind Terminal, encompassing 42 acres on the North Shore of Massachusetts, which will support expanded electrification capability as the state's second major offshore wind port terminal.

And this fall, the School of Engineering’s offshore wind graduate seminar series is focused on engaging with Tisch College through three seminars, two led by Cunningham and one led by Peter Levine, Lincoln Filene Professor of Citizenship and Public Affairs.

Both new endeavors come as Massachusetts is “all-in on offshore wind,” according to Governor Maura Healey. Vineyard Wind, the nation’s first commercial-scale offshore wind project, is projected to generate clean energy from 62 turbines to power more than 400,000 homes, part of a larger effort to help achieve the state’s goal of net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

But even with that ambitious goal, Massachusetts citizens can’t be an afterthought to progress, says Cunningham.

“One question of interest to us at Tisch College is how communities, policymakers, and others can thoughtfully make decisions that improve the economy for everybody, that share the benefit across the region, that don’t just accrue to wealthier neighborhoods or bigger businesses,” she adds. “How do we imagine a development trajectory that lifts all boats? These are among the decisions we can help communities think through.”

“The industry can move forward in a multitude of directions depending on the questions we ask,” she says.

From the beginning, Tufts graduate programs in offshore wind energy engineering, now in their sixth year, have taken a transdisciplinary approach to preparing students for varied career opportunities in offshore wind. While anchored in civil and environmental engineering, the graduate programs reflect their focus on systems thinking, spanning natural systems, technical systems, human systems and how they interact, says Hines.

It's fitting, he adds, that the introductory course, CEE-101, The Energy Transition, has no pre-requisites and is cross-listed between environmental studies, urban and environmental planning and The Fletcher School. This fall, to reach an even wider audience, the course is scaling up from 20 to 60 students.

“Civil and environmental engineering has a tradition of working across disciplines to get things done,” says Hines.

The graduate programs in offshore wind energy engineering also incorporate several electives in energy entrepreneurship, policy, economics, and management taught by Barbara Kates-Garnick, professor of the practice at The Fletcher School, and a former undersecretary of energy for Massachusetts.

Since 2016, Hines and Kates-Garnick have collaborated on the seminar Power Systems and Markets; their collaboration has yielded student-led research reports that have addressed critical logistics of the offshore wind industry buildout, including how to visualize grid interconnections and meet the rising demand for wind turbine installation rigs.

Working across schools, says Kates-Garnick, is “the advantage of Tufts: It enriches thinking to have the ability to integrate across disciplines to address the energy transition. Professor Hines recognizes that offshore wind is more than an engineering problem. It encompasses a wide range of tactical and strategic issues that affect how communities will be impacted by the state’s investment in sustainable, renewable energy.”

Her own approach to workforce development in the field is about raising awareness of the complexity of the systems, both on the conventional and renewable sides of energy and energy policy. “From my perspective, this transition to renewable energy is about all of us looking at each other in new and different ways and designing regulatory processes and new policy paradigms to facilitate and enhance participation among all those impacted by change,” says Kates-Garnick. “We’re all in this together.”

Looking ahead, Hines and Kates-Garnick will team up with Tisch College students to explore how civic-minded Tufts students can get involved.

Of particular interest are the coastal communities of Everett, Salem, Sandwich, and Somerset, all of which have shut down aging fossil-fuel energy plants and are now feasibly “points of new interconnection” for energy generated by wind power, Hines said, while also representing opportunities for Tisch College students to engage.

“It’s kind of amazing that these carbon-emitting power plants are finally gone,” he said. “But now what’s going to happen? How do we make the most of these incredible coastal connections to the grid? How do any of these changes happen? Every community has a slightly different role in the system, different populations and needs, and we all believe it goes well beyond technology and policy. Our work—across Engineering, Fletcher, and Tisch—is just beginning.”

Pictured above (left to right): Barbara Kates-Garnick, Dayna Cunningham, and Eric Hines